A Response to “Zero women can fight with a Sword”

The ahistorical and no doubt purposefully inflammatory drivel a conservative critic leveled at women fighting in the Netflix show “The Witcher” is undeserving of quotation. I’ll not share anything the ape said save what you read in the title. Interested parties can see the notes if they have the stomach for more—I will note that Forbes.com, which addressed this issue too, did cite the excellent example of London Longsword run by Dave Rawlings who, if you know him, would be (and was) quick to correct the ignorant critic (if you happen to see this, Hi Dave! =) [1]

The problem with poor excuses for Y chromosomes like this critic is that they have an audience. The pathetic incels who never leave their parents’ basements are one problem, but here I wish to address everyone else, general audiences with more wit, who might read that review and assume there is any veracity to it. There isn’t. I state this as both fencer and historian. A quick search online would’ve been enough to dispel Mr. Manly Man how incorrect his assessment of women using swords is, but it’s doubtful he cares. His point had nothing to do with truth or history and everything to do with pandering to his equally insecure base. Bad press is press, right?

There has been, rightly, enormous outcry about this. This is a good thing. Importantly, it’s not only been female fencers and fighters who’ve been quick to share examples of women with swords, but many of their male counterparts too. Now, more than ever, it is important for men—especially middle-aged white men like me—to stand up for their female colleagues and shout down the stupid. It’s as important as defending other historically marginalized colleagues such as People of Color and our comrades who are LGBT.

I know, firsthand, how difficult it can be trying to be an ally, but it’s important. You might also have difficulty overcoming how you look (something healthy for us old white dudes to experience from time to time); you might have someone’s unfortunate experiences with bad men grafted onto you, but that is part of advocacy. Not everyone sees you as an ally and some actively resent it. Some people will be happier using you as a convenient whipping post, especially if they’re unable to go after the men at work or in their families who have mistreated them. We all filter everything through our own experience. Do the right thing anyway.

Knowing my limitations, and my bailiwick, I’m trying to do my part as best I can. I tend to see my efforts to be a part of the solution as stumbling my way towards advocacy; I don’t claim to have all the answers or even most of them. But, I know A LOT of women who fence, as many if not more in martial arts generally, and I’ve been fighting alongside women since I first started studying the Art. As a colleague of female fencers, as the coach to several, I feel a responsibility to stand by them, and for the younger women I coach to serve as a good example.

I cannot and should not attempt to speak for women. However, I can hold up examples, ancient and modern, that put the half-baked notions of third-rate conservative critics in their proper light. The focus here will be on women and swords pre-20th century.

Women and Swords in History & Early Literature

There are a number of excellent examples in the historical record and in heroic literature. Granted, saga is not history, but it’s a repository of values, a glimpse into what a culture holds dear, how it sees itself or wishes to see itself. Greek authors—among them Homer, Aeschylus, Herodotus, and Diodorus of Sicily all mention the “Amazons.” Of note, while many are said to have lived in central Eurasia, Diodorus cites an example from what is today Libya. In each case, by the way, we have some evidence to suggest that these were not mere tales, but based at least in part on fact. Archaeology bears this out. For example, in the last twenty years archaeologists in the Ukraine have studied the graves of over 300 female warriors. The graves are replete with weapons, some contain horse sacrifices, and there is clear evidence from the human remains that these women used these weapons. The bulk of the graves date to the 7th cen. BCE too suggesting that Homer yet again drew from actual fact in his tale of Troy.

The Amazons mentioned in Classical stories are not isolated. Irish literature’s most celebrated warrior, Cú Chulainn, was trained by two female fight-masters, Scathach and Aoife. The most important Irish war deity, the Morrigan, one of a triad, was a goddess (as were the rest of the triad, Badb and Nemain). The Scandinavian Valkyries (possibly influenced by these Irish deities) were the female warriors of Odin who selected the valiant dead for Valhalla. The connection between female deities and war was widespread, as evidenced by the Greek Athena and Near Eastern Ishtar to name only two. Though perhaps less common than in saga (Medh jumps to mind) there are accounts of women among the Celts leading armies, most famously Boudicca (who led a revolt in Britain against Rome in the mid-first century CE). [2]

To this early evidence we can add several medieval and early modern exemplars who either fought or led troops. Here, in brief synopsis, are a few:

Sichelgaita of Salerno

The wife of the Norman leader Robert Guiscard, Sichelgaita is best known for her role in rallying the fleeing Norman soldiers at the Battle of Dyrrachium in 1081. According to the Byzantine chronicler Anna Comnena, she confronted her fellow soldiers and urged them to stop fleeing. “As they continued to run, she grasped a long spear and charged at full gallop against them. It brought them to their senses and they went back to fight.” Another chronicler adds that she was wounded by an arrow during the battle, but the Normans were able to defeat the Byzantines. A further look at her career finds that she took part in and commanded sieges and was more involved in her husband’s military activities than was previously known.

Joanna of Flanders

Joanna was known for her defense of the town of Hennebont in Brittany, against Charles, Count of Blois. After he had captured and imprisoned Joanna’s husband, he marched against the town in 1342. Joanna led the defense of the town. The chronicler Jean le Bel writes that “the brave countess was armed and armored and rode on a large horse from street to street, rallying everyone and summoning them to join the defense. She had asked the women of the town, the nobles as well as the others, to bring stones to the walls and to throw these on the attackers, as well as pots filled with lime.” The key moment of the siege was when she led 300 men out of Hennebont and burned down the enemy camp. She gained the nickname ‘Fiery Joanna’ for this feat. Joanna was able to hold off the besiegers until English troops arrived and forced the Count of Blois to retreat.

Jeanne Hachette

Jeanne “Hatchet” Laisne earned her nick-name defending Beauvais from the soldiers of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, in 1472. Like many women in the town, Jeanne grabbed a weapon to help defend the walls. She inspired her fellow defenders and famously fought against Charles’ standard-bearer.

Caterina Sforza

The Countess of Forli once said “if I must lose because I am a woman, I want to lose like a man.” A bold Italian noblewoman, Caterina was heavily involved in the papal politics of the late 15th century. Although her defense against a Venetian attack earned her the nickname ‘The Tiger of Forli’, in 1499 Pope Alexander VI sent his son Cesare Borgia to conquer her lands. Although she led a stout defense of Forli, she was eventually captured and taken back to Rome as a trophy.

Julie d’Aubigny

Julie d’Aubigny was a 17th cen. singer, actress, and swordswoman. Her father was a secretary to the Comte d’Armagnac, King Louis XIV’s Master of Horse, and an expert fencer who trained court pages at the Grande Écurie. He trained his daughter alongside the boys. Her career as a fencer is fascinating. At one point, after having run away from her lover (as well as a husband conveniently posted to the provinces), she worked with a fencing master and in men’s clothing assisted him with public demonstrations. When questioned about her sex, she removed her top to a stunned crowd. Perhaps her most famous encounter was a duel with three men at one time—once again in men’s clothing, she kissed a woman on the dance floor and was challenged. She beat all three.

Ella Hattan, “La Jaguarina”

Ella Hattan was born in 1859 in Ohio. She was a professional actress, but a trained fencer as well. She was a student of Colonel Thomas Monstery, a famous mercenary fencing master, and pugilist. Ever the actress, Hattan created “La Jaguarina,” a modern Amazon, and sought out men to fight in different fencing engagements. In 1888 she fought a mounted sabre duel with a Captain Weidermann, and dominated the entire bout. [3]

Women in Early Fight Texts

To the compelling evidence of women known to have fought we can add the evidence from extant fight manuals. Walpurgis, the female fighter in the earliest known western text about swordplay, Ms I 33, the Walpurgis Fechtbuch, heads the list. This collection of instructions for fighting with sword and buckler hails from early 14th century Germany and now resides in the archives of the Royal Armouries at Leeds. Significantly, Walpurgis, like the two other figures illustrated in the manuscript (the monk and scholar), is depicted fighting. She is not a spectator. She’s not serving refreshing mugs of beer or cheering them on. She is one of them, a fighter. [4]

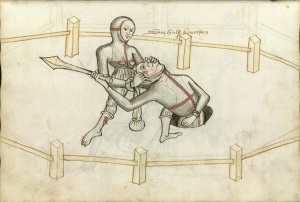

If you think she is an isolated case consider other well-known fight-books from Germany, perhaps most famously Talhoffer’s 1459 Fechtbuch (MS Thott.290.2º) which was produced in 1459. The images from 80 recto to 84 recto depict a woman engaged in a judicial duel with a man. With little explanation provided (the accompanying descriptions are terse) it can be difficult to appreciate what one sees here. Let’s start with the fact that women could fight judicial duels. Then consider that in these images we see her using not only a type of flail, but wrestling. In 82r she breaks his neck using the flail; in 82v he wins. However one look at this it’s clear that the female fighter is not completely out of her element. The man may start the fight in a small pit, but as we see their duel progress this woman clearly understands what she is doing, advantage or no. [5]

Addendum: One reader, Roderick, pointed out that I had neglected to include St. Joan d’Arc. This was not for any lack of respect for the saint. St. Joan not only led troops, but inspired them. She was often at the forefront of battle so her comrades as well as France’s enemies might see her. In fact, she was wounded on at least one occasion, and not even her enemies doubted her courage.

Women Fighting with Swords Today

Just as they have for centuries, many women in the modern world learn how to use swords (among other weapons), and, are damn good at it. Pick any field of fencing—Olympic, Classical/Historical, SCA, armored combat—and you will find women not only fighting, but teaching. There are organizations like Esfinges, a group dedicated to promoting and supporting women in historical fencing, and even events for women only. Women can and do fight with swords.

As fencers, as members of a small population often working in isolation, it’s on us to help dispel the misinformation so often associated with the Art, even when, as in this case, it’s obvious that the author’s comments were rhetoric intended for his own specious causes.

It may take different forms, we may pursue it differently, but the Art is for everyone.

NOTES:

[1] See among myriad recent responses https://www.forbes.com/sites/erikkain/2020/01/07/zero-women-can-fight-with-a-sword-claims-the-witcher-critic/#462c21751d8e. London Longsword, https://www.londonlongsword.com/

[2] For references in these authors, see for example Homer, “The Iliad,” 3.189, 6.186; Aeschylus, “Prometheus Bound,” §707 in Aeschylus, Translated by Herbert Weir Smyth, Loeb Classical Library Volumes 145 & 146, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1926; Herodotus, The Histories, IV: 110-117. For Cú Chulainn’s training and relationship with the goddess(es) of war see especially, Cecile O’ Rahilly, Táin Bó Cúailnge, Recension 1, Dublin, IR: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976; see also the excellent entries on the Morrigan et al in James MacKillop, A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998. For Boudicca’s revolt, key sources are Tacitus, The Annals, XIV, and Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXII: 1-2.

For a recent discussion of the “Amazons,” see https://www.npr.org/2020/01/12/795661047/remains-of-ancient-female-fighters-discovered. See also V.I. Guliaev, Amazons in the Scythia: New Finds at the Middle Don, Southern Russia,” in World Archaeology 35 (2003): 1, 112-125; Lyn Webster Wilde, On the Trail of the Woman Warriors: The Amazons in Myth and History, New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 1999.

For the Libyan example, see Diodorus Siculus, World History, 3.52-53; see also W.F.G. Lacroix, Africa in Antiquity: A Linguistic and Toponymic Analysis of Ptolemy’s Map of Africa, Saarbrücken: Verlag für Entwicklungspolitik, 1998.

[3] https://www.medievalists.net/2014/07/ten-medieval-warrior-women/. See especially the list of works consulted to produce this article (scroll down and you’ll find them).

For Julie d’Aubigny, a great resource in English is Kelly Gardiner’s website. She wrote a novel about d’Aubigny, Goddess, but did extensive research on her subject first. Cf. https://kellygardiner.com/fiction/books/goddess/the-real-life-of-julie-daubigny/

For La Jaguarina, see https://blogs.harvard.edu/houghton/la-jaguarina/; https://www.northatlanticbooks.com/blog/womens-history-spotlight-jaguarina-and-colonel-monstery/; Ken Mondschein, in Game of Thrones and the Medieval Art of War, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017, 171ff, discusses Hattan as well.

[4] See for example Folio 32r, https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Walpurgis_Fechtbuch_(MS_I.33)#/media/File:MS_I.33_32r.jpg. See also Jeffrey L. Forgeng, The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship: Royal Armouries MS I.33, Union City, CA: The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2003; Paul Wagner and Stephen Hand, Medieval Sword and Shield: The Combat System of Royal Armouries MS I.33, Union City, CA: The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2010.

[5] See for example https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Talhoffer_Fechtbuch_(MS_Thott.290.2%C2%BA). See also Hans Talhoffer, Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat, Translated and Edited by Mark Rector, London, UK: Greenhill Books, 1998.

Great article. You missed, however, St. Joan of Arc – surely one of the greatest military leaders in history, who turned the tide of war in France’s favour?

LikeLike

Hello Roderick, thank you for the kind words. The omission of St. Joan d’Arc does seem glaring, but it was not for any lack of respect for her. Though debate continues as to the degree of her personal involvement in the fighting, we know she rallied the French, wore armor, brandished a sword, and was wounded on several occasions. She was often at the forefront of battle to inspire, and even her enemies didn’t doubt her courage. You know, I think I will need to add her—recalling all she did, and endured, she certainly deserves to be listed.

LikeLike